Dr. R. Rajarajan

Abstract: The power and functioning of different branches of government is intertwined with their structure. A bicameral legislature function differently than unicameral. The powers of an executive headed by a President differs from that headed by a Prime Minister. The judiciary is no different. This article describes the architecture of the Indian judiciary–in other words, the different types of courts and judges in the Indian judicial system and the hierarchies and relations between them. In particular, it focuses on how the Indian judiciary coordinates its behavior through appeal and stare decisis and through a system of internal administrative control. Although the Indian judicial system, particularly the upper judiciary (i.e. the Supreme Court and High Courts), plays a central role in Indian political life and is widely covered in the media, there has been limited academic literature on the impact of the judiciary’s structure. The functioning of the Indian Supreme Court has only begun to be explored (Dhavan 1978; Robinson 2013), and even less attention has been given to India’s High Courts and subordinate judiciary (Dhavan 1986; Moog 2003: 1390; Krishnan et al 2014: 153).

Keywords: Rights, People, Activism, Participation and Justice.

INTRODUCTION:

The top-heaviness of the Indian judiciary is striking, both in terms of the relative power of the upper judiciary and the number of cases these courts hear in relation to the subordinate. The origins of this top-heaviness are partly historical. When writing the Indian Constitution the drafters emphasized that the upper judiciary should be accessible to ordinary Indians, especially to enforce constitutional claims. They also wrote in safeguards to protect the judiciary’s independence, giving Supreme Court and High Court judges a prominent role in court administration and the appointment of judges. After independence, both the accessibility and self-management of the upper judiciary have been further reinforced and strengthened through legislative action and judicial interpretation. Today, a broad distrust of the subordinate judiciary, both by litigants and judges of the upper judiciary, have led litigants to appeal from, or attempt to bypass, the subordinate judiciary in large numbers. As the Supreme Court in particular has become an omnivorous arbiter of last, and sometimes seemingly first, resort, it has seen an ever mounting number of matters before it, which has caused a multiplication of judges and benches. These different benches of the Supreme Court give slightly, and sometimes markedly, different interpretations of the Constitution and law more generally, generating confusion over precedent, creating even more incentive for litigants to appeal to the Supreme Court.

This top-heavy system has arguably aided the upper judiciary in its active involvement in large swaths of Indian political and social life. However, India’s disproportionate reliance on the upper judiciary has also slowed and added uncertainty to decision-making, contributing to the Indian judicial system’s well-known

underperformance on a range of measures from enforcing contracts to the duration of pretrial detention.

A Hierarchy of Courts:

On its face, the Indian Constitution organizes the country’s judicial system with a striking unity. Appeals progress up a set of hierarchically organized courts, whose judges interpret law under a single national constitution. Although states may pass their own laws, there are no separate state constitutions, and the same set of courts interprets both state and national law. At the top of the judicial system, there is a single Supreme Court. Upon closer scrutiny of this seeming cohesiveness, however, two types of clear divisions quickly become evident–that between the judiciary’s federal units and its different levels.

Each state in India has its own judicial service for the subordinate judiciary and judges of the High Court in a state are overwhelmingly selected from the state’s judicial service and the state High Court’s practicing bar. At the same time, each state provides funds for the operation of its judiciary. Since states in India are so socio-economically diverse this means that levels of funding for the judiciary can vary considerably, as can the legal cultures, litigant profile, and governance capability of different states. As a result, state judiciaries can perform strikingly differently in terms of professionalism, backlog, and other measures of functioning and quality.

In India, the upper judiciary is traditionally viewed not so much as an extension of the subordinate judiciary, but as categorically distinct–more capable, less corrupt, and with a more central role in enforcing constitutional rights. The judges in the upper judiciary tend to be from generally

more high status families and often have already had distinguished professional careers before joining the bench, unlike members of the subordinate judiciary who often join the judiciary directly from law school, making them less assertive and more likely to simply follow the arguments of more seasoned lawyers or the government (Galanter 1984: 481). Although court proceedings are mostly in

English in the upper judiciary, and the judgments always are, in the subordinate judiciary proceedings are often in the local vernacular, while decisions are in English (although they are frequently not reported).

Even at the nation’s framing, members of the Constituent Assembly, many of whom were lawyers in the High Courts, seemed distrustful of the quality and integrity of the district courts. The Constitution allows for litigants to directly petition the High Courts in constitutional matters (Article 226) and the Supreme Court if their fundamental rights are at stake (Article 32), although in recent years the Supreme Court has encouraged litigants to first approach the High Courts to remedy fundamental rights violations except for cases of national importance. Article 228 of the Constitution allows for a High Court to withdraw any matter involving a substantial question of constitutional law from a subordinate court to itself. MP Singh has argued Article 228 should not prohibit the subordinate courts from hearing certain limited types of constitutional matters, but in practice the High Courts and Supreme Court are the de facto constitutional courts of the country with the subordinate courts hearing few such cases (Singh 2012). Given the Constitution’s length and detail, along with the judiciary’s broad interpretation of it, many administrative law and other types of cases are considered constitutional matters and brought directly to the High Courts, further increasing the workload of the upper judiciary and further sidelining the subordinate courts.

A Description of the Courts:

The Supreme Court sits in New Delhi (Article 130). The Chief Justice may also direct that judges of the Court sit in other parts of the country with the approval of the President. There are longstanding demands from those elsewhere in India, particularly the south, for judges to sit in multiple locations as the Court disproportionately hears cases originating from Delhi and nearby states (Robinson JELS 2013: 587). However, the judges of the Supreme Court have traditionally resisted attempts to have benches outside the capital fearing such a practice would weaken the Court’s sense of institutional integrity.

In 2014 there were 24 High Courts in India, which ranged in size from 160 sanctioned judges in Allahabad to 3 in Sikkim. No state has more than one High Court (Article 214), but some High Courts have jurisdiction over multiple states (Article 231) and over union territories (Article 230). For example, the Bombay High Court is the

High Court for the states of Maharashtra and Goa and the Union Territories of Daman & Diu and Dadra & Nagar Haveli (two island groups off the western coast of India). Although the High Court’s principal seat is in Bombay, it also has benches that permanently sit in the state of Goa as well as two other large cities – Nagpur and Aurangabad – in Maharashtra.

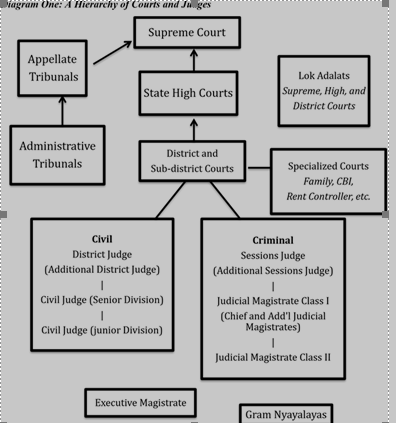

There are 640 districts in India each with its own district court. Additional sub district courts may operate at the block level. Some details that are not obvious from Diagram One are important to note. First, the diagram makes a clear distinction between judges on the civil and criminal side at the district level. In reality, a single judge will often wear both hats. For example, the top judge in the administrative hierarchy in a district court is called a District and Sessions Court Judge as she will hear both civil and criminal matters. Similarly, Civil Judges of the Senior or Junior Division are also often Chief Judicial Magistrates or Judicial Magistrates respectively. Although the District and Sessions Court Judge is the administrative head of the district she is otherwise a first amongst equals with Additional District and Sessions Court Judges in the same district. That is to say, the word “additional” in the title given to judges does not connote a lower rank.

Diagram one is only designed to give a general overview of the structure of the Indian judiciary. Historically there has been significant variation in the names used by different states to refer to types of judges and their grades and some of this nomenclature is still prevalent in parts of India, even if the overall judicial structure across the country is relatively similar. For instance, Junior Civil Judges are sometimes called Munsiffs and Senior Civil Judges are sometimes referred to as Subordinate Civil Judges.

There are also noteworthy differences between Diagram One and the court structure in metropolitan areas in metropolitan areas the distinction between Judicial Magistrates of the first or second-class is absent and they are collectively referred to as Metropolitan Magistrates. Further, Chief and Additional Chief Judicial Magistrates are referred to as Chief and Additional Chief Metropolitan Magistrates respectively.

The judicial service in the subordinate judiciary in a state will generally be broken up between the regular judicial service and the higher judicial service. District and sessions court judges will be in the more senior cadre while civil judges and magistrates will be in the lower cadre.

This distinction proves pertinent not just because it demarcates seniority, but because members of the bar can be recruited directly into the senior cadre if they have practiced as advocates for seven years or more (Article 233(2)).

In most states, original jurisdiction for both civil and criminal matters begins in the subordinate courts. Under the Code of Criminal Procedure, which applies across India, a magistrate of the second class may pass a sentence of imprisonment not exceeding a year, while a Chief Judicial Magistrate can pass a sentence not exceeding seven years. On the civil side, there is more state variation. Each state has a civil courts act under which a judge will have jurisdiction to hear a case depending on the monetary amount at stake in the suit. In the states with Presidency towns (Mumbai, Calcutta, and Chennai) and in New Delhi the High Court maintains original jurisdiction in civil matters above a certain amount or that originate in the old Presidency town itself. In the three Presidency towns, civil matters below such an amount are heard by the ‘City Civil Courts.’ Original jurisdiction civil matters in Mumbai, Calcutta, Madras, and New Delhi High Courts are heard in different courtrooms than appellate matters with High Court judges rotating between these courtrooms and respective jurisdictions. All high courts may also exercise extraordinary civil or criminal original jurisdiction at their discretion (Article 226).

District courts also frequently house family courts, juvenile courts, Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) courts, rent control courts, and other specialized courts created under specific legislation. Judges from the regular judicial service cadre will be appointed to these postings. For example, an Additional District Court Judge may be appointed as a principal judge in a family court. For some particular local areas, state governments may after consultation with the High Court of that state establish a special court staffed by judicial magistrates of the first or second class to try particular cases or classes of offences (for example, only murder or rape cases). Judges from the regular judicial cadre are also appointed to administrative posts (i.e., as court registrars and other key administrative staff in the judiciary).

Meanwhile, there are a number of tribunals, commissions, and courts whose judges are generally not drawn directly from the state judicial service, and instead have members that may be retired judges, former bureaucrats, social workers, or members of civil society. These non-cadre postings include consumer commissions, tax tribunals, administrative tribunals, labour courts, competition commissions, and environmental tribunals. Some of these tribunals are appealed to the High Court while others have specialized appellate bodies that may then be directly appealed to the Supreme Court. Litigants frequently attempt to bypass some of these tribunals (or the subordinate courts) by making a constitutional claim and bringing their matter directly to a High Court under its original jurisdiction for violations of fundamental rights.

CONCLUSION:

The Indian judiciary is a polycephalic creature – whose largest heads can snarl and sometimes bite – but which for much of its history has had an emaciated body. By centralizing power in the upper judiciary, and particularly the Supreme Court, the judiciary has helped protect and consolidate its independence, as well as corrected some of the worst errors of the rest of the judiciary. However, this top-heavy system has also led to promiscuous appeal, destabilizing stare decisis and creating more delay in the resolution of disputes. The interpretation of the Constitution, and law in general, frequently becomes polyvocal and in flux.

Today, India is investing more resources in its courts, including the subordinate judiciary. Nothing should be taken away from the critical role the High Courts and Supreme Court have played in checking some of the worst abuses or omissions of the state, but if the Indian judiciary is to truly be democratized it will be in the subordinate courts.

It is only judges at a more local level that can systematically ensure a citizen unfairly imprisoned by the police or a shopkeeper attempting to enforce a contract receives justice.

Empowering the subordinate courts will require reforming the top-heavy nature of the Indian judiciary. For instance, the Supreme Court could hear fewer regular hearing matters and have more large benches in order to provide clearer precedent for the entire judiciary, helping discourage appeal and encourage settlement. Subordinate courts could be allowed to hear at least some constitutional matters, while efforts could also be made to dismantle the rigid social hierarchy that creates undue servility in the subordinate judiciary in relation to the High Courts and Supreme Court (equalizing the retirement age for all judges would be one concrete place to begin).

Judges do not make judicial decisions in isolation. Instead, they sit within courts and professional hierarchies that shape and constrain their role in the adjudicatory process. Mapping the structure of this larger architecture helps us understand how both judges and litigants navigate this system and the context in which the law and the Constitution are ultimately interpreted.

REFERENCES:

- Upendra Baxi, The Travails of Stare Decisis in India, in Legal Change: Essays in Honour of Julius Stone (AR Blackshield ed. 1983)

- Upendra Baxi, Preface in the Shifting Scales of Justice: The Supreme Court in Neo-Liberal India (Mayur Suresh and Siddharth Narrain eds., 2014)

- Abhinav Chandrachud, An Empirical Study of the Supreme Court’s Composition, 46(1) Economic & Political Weekly 2011

- Chief Justices Conference 2009, Notes on Agenda Items, Aug. 14-15 (2009)

- Rajeev Dhavan, The Supreme Court Under Strain – The Challenge of Arrears (1978)

- Rajeev Dhavan, Litigation Explosion In India (1986)

- Theodore Eisenberg, Sital Kalantry, and Nick Robinson, Litigation as a Measure of Well Being, 62(2) Depaul Law Rev. 247 (2013)

- Marc Galanter, Competing Equalities: Law And The Backward Classes In India 481 (1984)

- Marc Galanter and Jayanth Krishnan, Bread for the Poor: Access to Justice and Rights of the Needy in India 55 Hastings Law J. 789 (2004)

- Marc Galanter and Nick Robinson, India’s Grand Advocates: a legal elite flourishing in the age of globalization, 20(3) Int’l J. of the Legal Prof. 241 (2014)

- Menaka Guruswamy and Aditya Singh, Village Courts in India: unconstitutional forums with unjust outcomes, 3(3) Journal of Asian Public Policy 281 (2010)

- Jayanth Krishnan et al. Grappling at the Grassroots: Access to Justice in India’s Lower Tier, 27 Harvard Hum. Rts. J. 151 (2014)

- Robert Moog, The Significance of Lower Courts in the Judicial Process, in The Oxford Indian Companion to Sociology and Anthropology (2003)

- Nick Robinson et al., Interpreting the Constitution: Indian Supreme Court Benches Since Independence, 46(9) Ec. & Pol. Weekly (Feb. 26, 2011)

- Nick Robinson, Structure Maters: The Impact of Court Structure on the Indian and U.S. Supreme Courts, 61(1) American J. of Comparative Law (2013)

- Nick Robinson, A Quantitative Analysis of the Indian Supreme Court’s Workload, 10(3) Journal Of Empirical Legal Studies 570 (2013)

- MP Singh, Situating the Constitution in the District Courts, 8 Delhi Judicial Academy Journal, 47 (2012)