Ioan S. Stratulat MD, (PhD) 1,2,3,4,5 Alexandru Chiriac MD, (PhD) 2,6 Roxana M. Căuneac7

Abstract: A subarachnoid hemorrhage can occur spontaneously, usually from a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. Treatment

is by prompt neurosurgery or radiologically guided interventions with medications and other treatments to help prevent

both recurrences of the bleeding and complications. Only a fifth of the patients has no residual symptoms. We present the

case of a 33-years old male patient that was referred to in the Neurosurgery Department of the Clinic Emergency Hospital

“N Prof. N. Oblu” Iasi, Romania with severe headache, nausea, and photophobia. The CT and angiogram performed

revealed a subarachnoid hemorrhage emerged from a ruptured aneurysm. The patient underwent endovascular

neurosurgery with minimal neurological complications. The rehabilitation protocol included psychological support, a

dietary regime with restriction of psycho-stimulants, and avoidance of psychoactive drugs, physiotherapy to gain muscle

strength, patient education concerning the reduction of stress and lifestyle changes. The symptoms were diminished during

hospitalization, muscle strength was increased. In this case, the outcome was excellent, the patient recovered 100% of his

motor function and neurological deficits. Common problems faced by patients following brain injury include physical

limitations and difficulties with thinking and memory. Recovery and prognosis are highly variable and largely dependent.

on the severity of the initial status.

Keywords: subarachnoid hemorrhage, physical medicine and rehabilitation, cerebral aneurysm.

INTRODUCTION:

A subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) represents a bleeding

into the subarachnoid space – the area between the

arachnoid membrane and the pia mater surrounding the

brain. This may occur spontaneously, usually from a

ruptured cerebral aneurysm. Treatment is by prompt

neurosurgery or radiological guided interventions with

medications and other treatments to help prevent

recurrence of the bleeding and complications. Immediate

complications include sudden death, vasospasm, rebleeding and hydrocephalus, long term complications.

include epilepsy, neurological symptoms, cognitive

impairment, anxiety, depression or post-traumatic stress

disorder. Only a fifth of the patients have no residual.

symptoms.

Quality-of-life assessments depend on clinical objective.

findings, but also on subjective aspects observed by the

patients themselves. Clinical findings are commonly based

on different scales that assess qualitative concepts: pain,

ability, functionality, severity of the disease. Since

aneurisms lead to a SAH similar to a traumatic one, the

same assessment scales are used in both cases. So, in order

to evaluate the global assessment of social outcome, the

Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) can be used (1). This scale

is commonly used for comparison between different

centers of outcome after different therapeutic regimens.

The scale has a five point assessment version,

recommended by Drake for SAH (2).

Subjective aspects refer to individual quality-of-life based

on life expectation: work abilities, family life and social

relations. Those aspects also rely on the psychological

changes that may result after a SAH, both as direct

complications related to the main location of the bleeding

and as complications of a post- traumatic disorder, a SAH

being an invalidating condition perceived as a traumatic event on an individual’s life. In order to assess those subjective aspects, an extended psychological evaluation is needed, using individualized psychological tests. Results should be interpreted after consultation with the patient’s family and friends in order to assess correctly any personality changes that might occur.

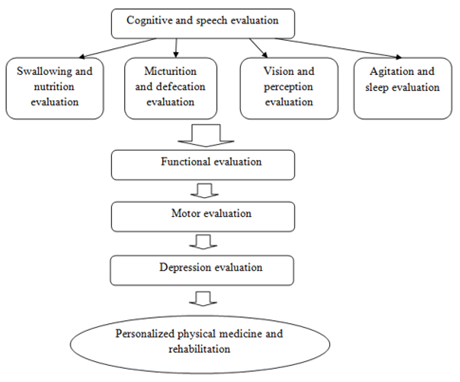

Rehabilitation after a SAH by aneurismal rupture represents a challenge since every case is unique. Therapeutic concepts in physical medicine and rehabilitation are a combination of methods used for stroke, traumatic brain injuries and psychiatric rehabilitation. Functional and psychological evaluation depends on the site of bleeding. A very important aspect that is frequently neglected is related to cognitive and emotional deficits; those aspects are extremely important, especially if we consider a young and active patient.

Last but not least, another important feature in assessment of the quality of life in this case is the ethical aspect. Professional commitment is based on the three fundamental principles stated by the American Board of Internal Medicine and the European Federation of Internal Medicine. It also involves an honest and appropriate relationship between the patients and their physician, and also the need for constant improvement of health-care, access to care and a just distribution of financial resources. The doctor is permanently in search for the best approach, constantly improving his knowledge.

MATERIAL AND METHOD – CASE PRESENTATION:

We present the case of a 33-years old male patient that presented in the Neurosurgery Department of the Clinic Emergency Hospital “N Prof. N. Oblu” Iasi, Romania with severe headache, nausea and photophobia, with acute onset 3 days before. The Hunt & Hess score at admission was 3, recovered to a 2 score the next day.

The CT and angiogram performed in emergency department revealed a subarachnoid hemorrhage emerged from a ruptured aneurysm.

Surgical technique:

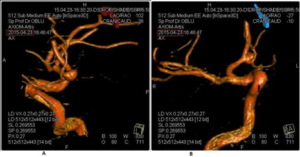

The angiogram exposed a 5/4 mm saccular aneurysm of the anterior communicant artery, with postero-superior orientation supplied by the right carotidian territory (Fig. 1).

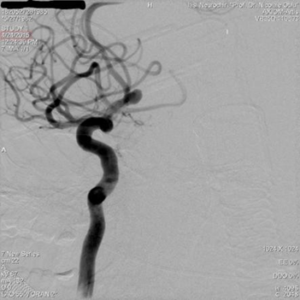

The next day, after a written consent from the family, the patient underwent endovascular neurosurgery (coiling technique) by right femoral approach, with a 6F sheath introducer and selective catheterization of the right internal carotid artery with 6F guide catheter Mach 1(Boston Scientific™) on 0.035” Radiofocus hydrophilic guide-supported (Terumo™). It is chose the optimum working position (see Fig. 2) with clear exposure of the aneurysmal package and A2 segments of bilateral anterior cerebral artery, both supplied by the right carotidian artery.

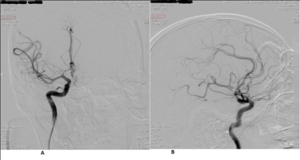

The aneurysm is microcatheterized in difficulty using Excelsior SL-10 (Stryker™) microcatheter, supported by 0.014″ Transend (Stryker™) microguide. After the microguides withdraw there were successively introduced and detached 5 GDC-10 spirals with angiographic occlusion of the aneurysmal sack. After introduction and placement of the first spiral 5000 IU of heparin were administered. Finally the microcatheter is withdrawn carefully from the aneurysm, and the front and profile position of the aneurysm occlusion are checked by DSA acquisition.

Then, the guide catheter is withdrawn by aspiration; the access sheath is removed, with topical compressive dressing. A control angiogram is obtained, showing the correct placement of the spirals inside the aneurysm (Fig. 3).

Neurological complications occurred were minimal-right Abducens nerve (VI) paralysis – diplopia with nistagmus and dizziness at lateral view, slight motor deficit on the right arm and leg with minimum reduction of muscle strength (4/5).

The patient was able to start the rehabilitation protocol the next day after surgery in the intensive care unit, with passive mobilization and short session of gentle massage. After 10 days of intensive medical treatment to prevent the vasospasm, the patient started the rehabilitation program in the neurosurgery unit, and after 3 weeks, he was transferred to the rehabilitation department.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS:

Personalized Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation protocol:

Table 1: Physical medicine and rehabilitation protocol with applicability for the case

Rehabilitation | Applicability for the case |

1. Cognitive and speech rehabilitation | Attention and orientation deficits |

2. Swallowing and nutrition | No impairment present |

3. Micturition and defecation | No impairment present |

4. Vision and perception evaluation | Diplopia due to abducens nerve palsy |

5. Agitation and sleep | No impairment present |

6. Functional evaluation | Functional score at admission in the rehabilitation unit: 193 |

7. Motor rehabilitation -upper limb – gait -other interventions | Slight motor deficit in right arm and leg |

8. Depression evaluation | No impairment present |

- Cognitive and evaluation:

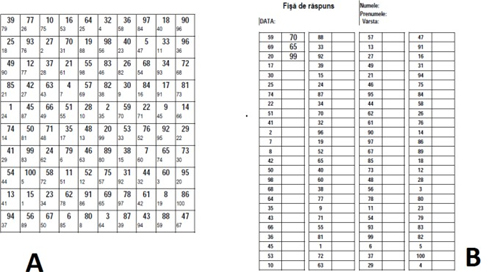

For the cognitive performance, we used a number of psychological tests: the Prague test for distributive attention and the Toulouse test for focused attention.

The Prague test (Fig. 5) was elaborated by the Psycho-technical Institute of Prague. This test consists of two pages: on the left there is a square divided in 100 squares of 1 centimeter; each small square contains a number written in bold, there are printed numbers from 1-100, placed into disarray after scattering probability. Each number in bold is accompanied by a small number printed in the bottom right corner of each small square. On the right there are four vertical columns; they are divided, in turn, in two columns: the first contains a number and the other is left free to be completed by the subject: he has to examine in turn each number in the column, to look on the left page among the numbers in bold, to see which is the number written in bottom right corner of the square and write it in place.

The Toulouse test is similar to the Prague test, consisting in a series of different squares with similar shapes and minimal differences. The patient is asked to find specific squares in a row of other similar squares.

We performed these evaluation tests at admission in the rehabilitation department, at discharge and follow-up at 1, 3 and 6 months.

For the Prague test, the results are divided into four stages of 4 minutes each, testing both attention and endurance in periods of psychical stress. The results are expressed in percentage. At admission, the Prague total test score was 60%, due to limitation of both attention and sight because of the diplopia. At discharge, the score increased to 75%, and at the 6 months follow-up the score was 90%.

For the Toulouse test, the results were similar.

2. Swallowing, nutrition, urinary function, defecation, vision and perception evaluation:

Patients suffering from a traumatic brain injury – therefore those with SAH after a cerebral aneurism – often express increased nutritional needs due to increased energetic expenditure but also due to increased proteic loss. Monitoring the nutritional status includes laboratory data, periodically weighing and even more complex studies such as metabolism measurements. Patients suffering from a swallowing disorder often need assisted nutrition by gastric or intestinal tubes. The choice between a gastric and an intestinal tube is usually based on the presence of the gastro-esophageal reflux.

In our case, the patient’s condition did not suppose any swallowing or nutrition problems. Initial immobilization in the intensive care unit was minimal, the rehabilitation was started early, so the weight loss due to immobilization was minimal and there were no nutritional problems.

Urinary and intestinal function impairment are often seen in those cases (3). Dysfunctions of the urinary tract lead to prolonged hospitalization or long-time care in an institution or at home. These factors lead to infections that complicate even more the rehabilitation for this type of patient and affect the long-time outcome. Initial assessment of the urinary function began the second day after surgery when the catheter was removed. The patient had no dysfunction of the urinary tract and the intestinal function was normal.

Vision and perception assessment revealed diplopia due to right abducens nerve palsy. This dysfunction also persisted at admission in the rehabilitation unit and also at discharge, and partially remitted at the 3-months follow-up. Due to this impairment, the patient suffered some orientation and attention dysfunctions. For rehabilitation, facial massage and ocular gymnastics were performed twice a day from the admission in the rehabilitation unit. At discharge, the patient continued the massage and exercises at home under close supervision. Disappearance of diplopia

was partially observed at the three months follow-up, and the remission was completed after four months. The patient was instructed not to perform activities that involve attention, concentration or orientation, such as driving, until the six-month follow-up.

3. Behavioral evaluation:

Alteration in emotional and behavioral status of these patients are common in the acute phase, and often consist of agitation and sleep disorders (4,5). Agitation was an important aspect in this case and was monitored closely, because as a common complication of a SAH it represents a challenge for the family and also the physical medicine and rehabilitation team. In our case, we closely monitored the patient, tracking every possible mood change: irritation, anxiety, aggressivity, disinhibition. The only change that was observed was a slight lack of attention that was closely supervised and improved by the 3-months follow- up.

4. Functional and motor evaluation:

We used the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) and the Functional Assessment Measure (FAM). These scores are used to evaluate the initial functionality but also the progress of rehabilitation, the efficacy of therapy and to take appropriate discharge decisions. For the best assessment of functionality, we used the combined scale – the UK FIM+FAM Group Scale, developed in UK in 1999 (6) (Table 2).

The functional score at admission was 193, at discharge 200 and at three months after discharge the score was 207.

Motor evaluation revealed slight motor deficit on the right arm and leg with minimum reduction of muscle strength (4/5). Aerobic exercises to increase muscle strength were started at admission in the rehabilitation unit, and were continued after discharge at home, under close supervision. At the three-month follow-up, the patient had no residual motor deficit.

Table 2: The UK FIM+FAM Scale

| Admission | Discharge | 3 months follow- up | |

| 1. Self-care: | |||

| Eating | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Grooming | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Bathing/showering | 5 | 7 | 7 |

| Dressing upper body | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| dressing lower body | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Toileting | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Swallowing | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| 2. Sphincters: | |||

| Bladder management | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Bowel management | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| 3. Mobility: | |||

| Transfer: bed-chair/ wheelchair | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Transfer: toilet | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Transfer: shower/bathtub | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Transfer: car | 6 | 6 | 7` |

| Locomotion: walking | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Locomotion: stairs | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Community mobility | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| 4. Communication: | |||

| Expression | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Comprehension | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Reading | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Writing | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Speech intelligibility | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| 5. Psychosocial: | |||

| Social interaction | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Emotional status | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Adjustment to limitations | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Use of leisure time/ employability | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| 6. Cognition: | |||

| Problem solving | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Memory | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Orientation | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Concentration/attention | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Safety awareness | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Scoring: | |||

| 7 Complete independence: Fully independent 6 Modified independence: Requiring the use of a device but no physical help 5 Supervision: Requiring only standby assistance or verbal prompting or help with set-up 4 Minimal assistance: Requiring incidental hands-on help only (subject performs > 75% of the task) 3 Moderate assistance: Subject still performs 50–75% of the task 2 Maximal assistance: Subject provides less than half of the effort (25–49%) 1 Total assistance: Subject contributes < 25% of the effort or is unable to do the task |

5. Emotional evaluation:

Another important aspect in our case was the evaluation and control of the emotional status. Depression is one of the most common psychological problem after a traumatic event such as SAH (7,8,9). The psyche of the patient is as important in the healing process as administered drugs.

The patient was monitored by the rehabilitation team and underwent intensive psychological support during hospitalization and after discharge. Early social reinsertion and early return to his work duties with reduced responsibilities helped in the prevention of depression.

CONCLUSION:

- In this case, the outcome was excellent, the patient recovered 100% his motor function and neurological deficits. This was due to early diagnostic and excellent evaluation in the first 24 and 48 hours.

- Excellent initial management by the neurosurgery team and the facilities in the neurosurgery department allowed that the physical medicine and rehabilitation protocol was started in the first day after surgery, minimizing immobilization periods and, thus the complications.

- The 3 months follow-up revealed partial remission of diplopia, the disappearance of nistagmus and dizziness, and improvement in the psychological status. The 6 months follow-up revealed perfect stabilization of the embolization coils, disappearance of the diplopia and only a few attention and memory deficiencies.

- Psychological tests revealed minimal deficits of attention, concentration and orientation, with no impact on the social life and work abilities. Therefore, the absence from work was minimal, and at reinsertion no impediments were encountered.

- The key for success was the compliance of protocols, a good neurosurgery team and a focused rehabilitation protocol personalized by the physical medicine and rehabilitation team.

REFERENCES:

- Svensson E, Starmark J-E (2002): Evaluation of individual and group changes in social outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: a long-term follow-up study. J Rehabil Med; 34: p. 251-259.

- Drake CG (1988): Report of World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies Committee on a universal subarachnoid haemorrhage grading scale. J Neurosurg; 68: p. 985–986.

- Foxx-Orestein A, Kolakowsky-Hayner S, Marwitz JH, et al (2003): Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of fecal incontinence after acute brain injury: findings from the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems national database, Arch Phys Med Rehabil 84: p. 231-237.

- Bogner J, Corrigan JD (1995): Epidemiology of agitation following brain injury, Neurorehabilitation 5: p. 293-297.

- Coll P, Erikson RV (1989): Mood disorders associated with stroke, Phys Med Rehabil State Art Rev 3: p. 619-628.

- Turner-Stokes L, Nyein K, Turner-Stokes T et al (1999): The UK FIM+FAM: development and evaluation. Clin Rehabil.; 13: p. 277–87.

- Fedoroff JP, Starkenstein SE, Forrester AW, et al (1992): Depression in patients with acute traumatic brain injury, Am J Psychiatry 149: p. 918-923.

- Rogers JM, Read CA (2007): Psychiatric comorbidity following traumatic brain injury, Brain Inj 21: p. 1321-1333.

- Binder LM (1984): Emotional problems after stroke, Stroke 15: p. 174-177.